Carlye Watt, Head Baker, Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop, Anchorage, Alaska

BreadLines, the journal of the Bread Bakers Guild of America just published (Summer 2018) my article about Carlyle Watt, head baker at Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop. You may also know Carlyle as one of the founders and chief musicians of the Anchorage group Super Saturated Sugar Strings. They’re described as “Americana-meets-chamber-ensemble,” and a “soul-shaking, infinitely charming band.” Carlyle’s as great a baker as a musician, and the James Beard Foundation recognized this in 2017 when they nominated him for an Outstanding Baker award.

Alaska’s Gold Rush sourdoughs never had it so good. A shiny new stone-grinding mill. Local wheat in Alaska of all places. A James Beard nominee for Outstanding Baker with an alternate identity as lead guitarist in an Alt Folk Rock band. Anchorageites can find it all at Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop, a sunny bakery near downtown.

Carlyle Watt, head baker, hands me a chunk of his Alaska Sourdough bread. “I’ve been playing with different formulas, trying to push the hydration.” I approve. It’s moist, full of flavor, and with a properly crackling crust. We are standing on the sidewalk in one of Anchorage’s older neighborhoods, filled with rustic log cabins, and renovated 1950s frame houses. Wrapped in their lush summer greens, the Chugach Mountains rise in the east, and ocean fragrance drifts from the west. Geraniums overflow their hanging baskets, and tourists mingle with locals at the outdoor tables. Scents of loaves fresh from the ovens overtake even the flowers.

Carlyle checking out experimental wheat at the UAF Experimental Farm near Palmer

Carlyle has been experimenting during the past few months with wheat from Ben and Suus VanderWeele’s farm in the Matanuska Valley; with a still-new custom-built stone-wheel Meadows Mills machine; and with mixing other Alaska grains into his doughs to create an Alaska Terroir loaf. His James Beard Outstanding Baker nomination in 2017 is a rarity for the state. The judges’ decision recognizes his creativity in baking breads, and his search for local grains and produce to incorporate into the bakery’s offerings.

Carlyle draws on varied influences. His roots sink deep into his family’s South Carolina Low Country food traditions. He trained at the Culinary Institute of America’s Greystone Campus in California. While in school, he learned breads by going to classes during the day and baking for the school’s Wine Spectator Restaurant until 4:00 a.m. Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop owners Jerry Lewanski, Janis Fleischman, and their daughter Rachel Pennington rely on his inventiveness with breads, his persistence, and his contributions to their expanding savory menu.

The custom-built mill is a recent acquisition. Meadows Mills in Wilkesboro, North Carolina built the mill to Fire Island’s specifications. It arrived in early March of 2017. Nine months later, Carlyle is still experimenting with settings for different grains, accounting for changes in the weather, and thinking about styles of breads. He’s trying to stop spillage from the mill, and the bakery crew are still learning how to understand the wheat’s moods each day.

With two 12-inch natural burr stones, the mill should grind 150 pounds of flour each hour. Carlyle wants the flour milled fine, especially because it’s whole wheat. “The finer you mill the wheat, the more water that it can absorb. The yeasts move more freely, eating up more of the flour’s natural sugars. Carlyle likes the fresh-milled flavors, and the health benefits of the added germ and bran. He can keep those because he grinds just enough wheat for each day’s baking. The freshness and using the whole grain means that he can do a 90% hydration. His experiments show that any more hydration and the dough loses its structure; any less and the crumb is too dry.

Fire Island works closely with the Bread Lab at Washington State University, sending the local wheats for analysis and testing. “They tell us that Alaska wheat tastes different,” says Carlyle. “It’s the clean glacial soil. Because Alaska is far from pests common to wheat in other parts of the world, and the land hasn’t been farmed until the past 80 years, we haven’t needed pesticides and herbicides.”

Ben and Suus VanderWeele, a Dutch couple who have been farming in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley for fifty years, would agree with the Bread Lab. They provide Fire Island’s local wheat; the bakery also uses organic flours from Central Milling. This year theVanderWeeles grew “Glenn,” a spring hard red wheat developed in North Dakota in 2005, and provided by Rob Carter at the Alaska Plant Materials Center. Its 12% – 14% protein make it ideal for Carlyle’s whole-wheat sourdough.

Ben VanderWeele’s wheat, to the right; potatoes on the left; Chugach mountains in the back (July 14, 2018)

VanderWeeles also grew “Ingal” in 2017. Its Alaskan ancestry stretches back more than a hundred years to George Gasser, one of the earliest wheat researchers in the state. Because Ingal is a softer grain, Carlyle is eager to try out in pastries and other breads. Right now, he’s using it in muffins. Much of this year’s crop went to Alaska breweries and distilleries that prefer lower-gluten for a clearer brew. There will be more in 2018.

Carlyle’s working on an Alaska loaf that combines the tastes of rye from VanderWeeles with barley from long-time farmer Bryce Wrigley in Delta Junction. He muses that it might include barley porridge too, or couscous made from cracked barley, or oats from local sources. Barley by itself ferments too fast, but combined with the other grains develops slowly enough to make a shapely and moist loaf.

Carlyle didn’t come to be head baker at Fire Island Rustic Bakeshop by any expected route. He arrived in Alaska as a personal chef, and met his cellist wife. They formed The Super-Saturated Sugar Strings with several other artists, and toured the Northwest for three months. Back in Alaska and broke, Carlyle went to Janis Fleischman at Fire Island and negotiated for a job that would allow him to create breads in the early part of the day and play music later on. “They accommodate my schedule. I am lucky to work for people who share a passion for quality baking and the ideals associated with getting the most ethical ingredients into our shop. Janis, Jerry, and Rachel push me to be better every day. They also give us the tools and equipment necessary to succeed,” he says. “It’s symbiotic: the music probably changes the way I bake, and baking enriches my music.”

The Super Saturated Sugar Strings, with its guitar and cello, and bass, keyboard, trumpet, and violin is one of Anchorage’s best –rated bands. It’s as much in demand as Carlyle’s sourdough breads and savory creations at Fire Island – think Lucky Wishbone scones, made with the best local deep-fried chicken. He pushes his trademark newsboy hat back as he hands me a last piece of focaccia to test. He’s not making with VanderWeele’s wheat yet, but with luck that will happen soon.

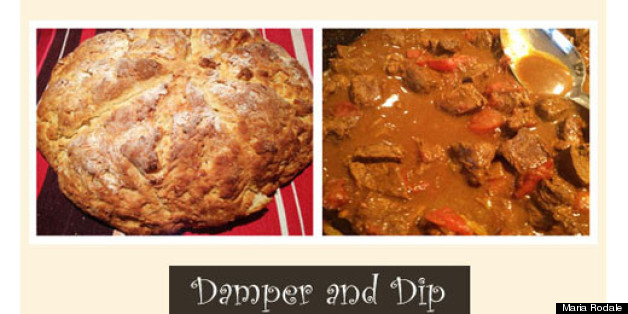

Fire Island’s Alaska Beet Sourdough

Alaska has a bit of a beet problem – too much of a good thing. Farmers struggle to get the storage crop sold before harvesting the next crop early in the fall. Diners tire of beet and goat cheese salads, so we get creative and bake beet sourdough loaves. Steam the beets before pureeing them to get the brightest ruby color in the crust. Red and brown marbling in the moist crumb, complex taste, and the standout crust color combine for a bread that people look forward to every week.

Alaska Beets (August 4, 2018).

Steam beets until tender, roughly 1.5-2 hours. Cool to room temperature. Peel and puree in a food processor until smooth.

Total Dough Weight 7.500 kg

Levain

5% of total flour

Artisan Baker’s Craft: 100% .090g

Water: 100% .090g

Starter: 10% .009g

Final Dough

Artisan Baker’s Craft: 90% 3.600k

Whole Wheat Flour: 10% .400

Salt: 2.5% .100

Water: 80% 3.200

Starter: 5% .200

Raw beets: 40% 1.600

Levain

Mixing By Hand

Length of Time Until Incorporated

Fermentation Time 6-8 hours 72-76F

Mixing

Type Mixer: Spiral

Mix style: Short

Hold Back Salt and Beet Puree

1st Speed: 5 minutes

Autolyze: 20 minutes

1st Speed 20 minutes

Add Salt and beet puree 5 minutes

Dough Temperature: 76-78F

Fermentation

Time/Temperature: 3-4 hours at 72-78F

Number of Folds: 3

Timing of folds: 0:30

Shaping

Divide: 750g

Preshape: Round

Rest: 0:20

Final Shape: Boule

Proofing Device: Banneton dusted with white flour

Proof

Time/Temperature: 1 hour at 76F

12-18 hours at 43F

Bake

Oven Type: Deck

Steam: 2 sec, 3 sec

Time/Temperature: 0:32 at 240 C (32 minutes, approximately, at 460 Fahrenheit).